Ernest William Jarvis

Ernest William Jarvis was born in Felsted in the final

quarter of 1893. The second son of Arthur and Lucy Jarvis.

Ernest William Jarvis was born in Felsted in the final

quarter of 1893. The second son of Arthur and Lucy Jarvis.

By the outbreak of the war the family had moved to Chelmsford where Ernest worked in a shop.

He was conscripted in 1916 and served as private soldier 50473 with the 8th Battalion the Suffolk Regiment, and was later transferred to be private soldier 40413 with the 1st Battalion of the Royal Dublin Fusiliers.

In 1916 Ernest married Edith May Halls in Chelmsford and they had a daughter Beryl, who sadly never knew her Father.

Ernest died on 24th April 1917. Having no known grave he is remembered on the Arras Memorial.

He is not commemorated in Felsted, but is remembered in Chelmsford Cathedral and in the list of the fallen at the Civic Centre.

Ernest William Jarvis is also remembered on St. Andrewís Church Boreham WW1 memorial plaque.

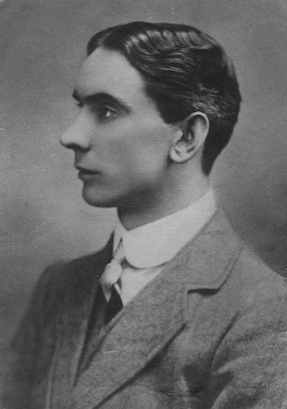

Chris Weekes the great nephew of Ernest has written the following article, and kindly provided the photograph:

by Chris Weekes

My grandmother Winifred, was born into the extended Jarvis family of Felsted Essex in 1902. She had 4 brothers Albert, Ernest, Stanley and Perce. Albert emigrated to Canada at the age of 14 before my grandmother was born whilst Stan and Perce were too young to be called up for military service during WW1. Ernest was the second oldest in the Jarvis family of Wood Farm Felsted having been born in 1880.

When the war came in August 1914, Ernest had moved from the farm life to live in the county town , Chelmsford working in the local store of Luckin Smiths. From my grand motherís description of Ernest it seems that he was not cut out for the physical exertions of farm life preferring to live and work in a town. Unlike his cousins in the Jarvis and Livermore families, Ernest had not reacted to his countryís call to arms in 1914 and in fact he told his sister Winifred that he did not want to go into the army. In January 1916 the Military Services Act brought in conscription as the numbers of volunteers began to dry up and thus it was that Ernest the reluctant soldier found himself in the Training Reserve.

Regrettably, his army service records do not exist but the database of Soldiers Died in the Great War 1914 /1919 shows that he enlisted at Chelmsford and went into the Training reserve number 9342 and could have been in the 10th ( Reserve battalion ) based in Harwich. The same data base shows that he died on 24/4/1917 whilst serving in the 1st Battalion Royal Dublin Fusiliers ( RDF ) private 40413. However , his Medal index card shows that whilst he died serving with the RDF, he had also been in the Suffolk regiment number 50473. Thus it appears that Ernest had initially joined a local regiment and at some point had been transferred to an Irish regiment in the 29th Infantry Division famous for its involvement in the Gallipoli campaign

A visit to the National Archives at Kew enabled me to examine the Medal roll for the Royal Dublin Fusiliers which confirmed that Ernest Jarvis was private 40413 and had previously been private 50473 in the 8th battalion of the Suffolks. On the same page of this medal roll it showed a number of other men who had been in the 8th Suffolks and then transferred to the 1st RDF. Further researches into the Medal Roll showed that 36 men had transferred from the Suffolks to the RDF and there is a sequence of service numbers from 50468 to 50488 of the 2nd and 8th battalions the Suffolk regiment who became RDF men with service numbers from 40400 to 40420 ( my Great uncle was 40413 ).

I will return to this link between the Suffolks and the Dubliners at a later stage.

So , when precisely did Ernest Jarvis ,the reluctant soldier, go to France. The Suffolk regiment records are held at the Public records office in Bury St Edmunds. Whilst there are no lists of servicemen and no sequencing of service numbers, information from a regimental expert suggests that Ernest joined the 8th battalion Suffolks in May 1916 after his period in the Training Reserve and training in France possibly at the notorious Etaples Bull Ring .In fact in the battalion war diary WO95/2039, an entry for May 28th 1916 refers to 48 other ranks ( ORs ) joining the battalion. The 8th Suffolks were in the 53rd brigade of the 18th ( Eastern ) Division under Ivor Maxse who proved himself to be one of the very best divisional and later corps commanders of WW1 . The 18th Division was based around Carnoy and Bray in the southern part of the Somme sector leading up to the battle of the Somme. On the fateful day of July 1st 1916 the 53rd brigade was in reserve to the 55th and helped in the capture of Montauban Alley by carrying up water and supplies. On the first day of the Battle of the Somme, the 18th Division lost 3300 casualties so that Ernest and the 8th Suffolks had been lucky not to have been in the forefront of the attack.

The Somme continued with attack and counter attacks and on 18th July Ernest and his fellow Suffolk boys were involved in the task of trying to take Delville Wood. One of the many woods dotted about the battle zone and whose names have been attached to bloody fighting, Delville Wood has gone down in history as the scene of the massive slaughter involving the South African brigade. On the 18th July the 53rd infantry brigade was given the task of extricating the South Africans from their precarious position in the wood . The 8th Suffolks were set the objective of clearing the Germans out of Longueval village. They were involved in two days of intense defensive fighting as the Germans refused to give any ground. As the war diary tells us , "A company of 8th Suffolks did manage to relieve a detachment of South Africans on the edge of Delville Wood but by 4 30 pm on July 19th owing to severe losses from both shell and machine gun fire the attack failed in its entirety and the men were not in a position to make a further assault." By 6 am on 21st July the 8th Suffolks had been relieved by the 4th Royal Fusilers and were out of the battle zone.

For Ernest and the others August brought a respite from the horrors of the Somme as they rested in the Armentieres area and trained waiting for their next task. This turned out to be the attack on Thiepval, the fortified village that had withstood numerous efforts to take it from the early part of the war. On July 1st the 36th Ulster Division had almost taken it but had to withdraw because of a lack of support on its flanks. A testimony to their sacrifice is shown by the many cemeteries around the area and to the Ulster Tower standing near to their attack position. It is no coincidence that the place chosen for the Memorial to the Missing of the Somme should be Thiepval as it dominates the surrounding rolling countryside.

In late September the 18th Division practiced for the attack at Varennes south east of Thiepval where the whole trench system had been reconstructed.

As the 18th Divisional history tells us , the preparation for the battle was extremely thorough. Officers were carried by a fleet of buses to the area to familiarize themselves with the terrain. The trench systems were completely renovated by the Engineers and the Royal Sussex Pioneers who dug new assembly trenches for the 53 and 54th attacking brigades. All this work was done on 4 nights before the attack scheduled for 26th September. General Maxse was a perfectionist and his doctrine was ď without proper preparation the bravest troops fail and their heroism is wasted ď A doctrine much appreciated by his men but not always followed by his fellow generals of WW1.

The 8th battalion Suffolk war diary provides a very detailed account of the Thiepval battle and its preparations. "the 18th division attack to be carried out by the 53rd brigade with the 8th Suffolks on the right and the 10th Essex on the left. Every rifleman to carry 170 rounds into battle with haversack tools water bottle and two days rations."

The IInd Corps attack was carried out by the 11th and 18th divisions. The 18th was on the left and the 8th Suffolks were in the forefront . Zero hour was scheduled for 12 35 pm on 26th September 1916 and not the usual dawn attack. The attack was preceded by 3 days of artillery barrage using 105000 rounds including gas. The Suffolks were given the objective of taking the Schwaben Redoubt which was heavily fortified and had with stood the July 1st bombardment. Interestingly Thiepval was garrisoned by the same German regiment since 1914, the 180th Regiment of Wurtembergers survivors of the original 1914 German army. At first the Suffolks reached the objective without casualties and the 27th September was spent in consolidation. On the 28th the Corps attacked the Schwaben redoubt with the 8th Suffolks the only regiment from the 53rd brigade strong enough in numbers to be used. By 2.30 pm on 28th the Suffolks had gained a foothold in the Scwaben redoubt. The battle for the complex system of trenches went on with bombing parties trying to knock out the nests of machine guns .All the regiments of the 18th Division were used to capture the Scwaben Redoubt and beyond. Into October the fierce hand to hand fighting continued and the shelling and incessant rain turned the whole landscape into a sea of mud so familiar to the soldiers of WW1. On 5th October after the Schwaben Redoubt had been taken the 18th division was relieved by the 39th having suffered 1990 casualties in 8 days of extreme fighting . All the troops had performed well and General Maxse paid especial tribute to the discipline steadiness and fighting qualities of the 8th Suffolks. As the Suffloks Regimental History says "It was perhaps its finest achievement of the war."

Haig visited Maxse and expressed his appreciation "Thiepval has withstood all attacks on it for exactly 2 years and it is a great honour to your division to have captured the whole of this strongly fortified village at the first attempt. Hearty congratulations to you all."

Ernest had survived the struggle for Thiepval although the 8th Battalion had lost 208 men some of whom are buried nearby in the CWGC Mill Road cemetery which has the unusual feature of the grave stones being laid flat on the ground because of the risk of subsidence caused by the many tunnels under that part of the old battle field.

During October and November 1916, Ernest and the 8th Suffolks were around Albert and in and out of the front line trenches in front of

Regina trench. On 16th October an attack on Regina Trench was postponed until 21st and when it was eventually taken the 8th Suffolks had been withdrawn and took no further part in the battle of the Somme. The remainder of 1916 was spent in training around Hautvillers north of Abbeville.

Ernest had been in France for 7 months when in December he went back to the UK on leave and to marry Edith May Halls in Chelmsford. This is confirmed in the marriage records on Ancestry and the fact that my grandmother and Ernestís sister had memories of the wedding. It was during this time that he told his family just how much he hated being a soldier reflecting the horrific things that he had seen and been involved in. Given that the normal period of leave was a week though there may have been extensions for marriages, we can assume that he had to return to the front sometime in January 1917.

However, like so many others in the later stages of the war returning from leave meant a transfer to another unit in his case a very famous regiment of the British army, the Royal Dublin Fusiliers. At the out break of the war in 1914 the 1st battalion of the RDF was in Madras as part of the Indian army. On 19th November it sailed from Bombay to Plymouth where it joined the 86th brigade of the 29th Division. This then sailed from Avonmouth to Alexandria and then landed at Helles on 25th April 1915 as part of the Dardenelles campaign. The casualties were so heavy that at one point it had to join up with the 1st Royal Munster Fusiliers to form a battalion known as the Dubsters. After being reconstituted as the 1st battalion RDF, it left Gallipoli on 1st January 1916 arriving in Marseilles on 19th March 1916. It was then involved with the other regiments of the 86th brigade in day one of the Battle of the Somme attacking Beaumont Hamel following the explosion of the Hawthorn ridge mine and experiencing a high casualty rate. Part of the 29th Division was the Newfoundland regiment commemorated today at the Newfoundland Park Beaumont Hamel.

Being an Irish regiment the RDF had relied upon volunteers from the South of Ireland but after the initial burst of enthusiasm the number of volunteers failed to keep pace with the casualty rates. The South of Ireland with its domestic troubles after the Easter rising of 1916, did not have conscription so that by 1917 many non Irish soldiers had to be drafted into the Irish regiments. Thus Ernest Jarvis formerly private 50473 8th battalion Suffolks became private 40413 1st Battalion RDF and went into W or X company. My researches into the war diary of the 1st RDF WO95/2301 shows that between 1st January and 5th April 1917, the battalion received 397 ORs and looking at the Medal Rolls shows that at least 36 men from the Suffolk regiment were transferred. Of these 36 there were 8 from the 8th battalion Suffolks with regimental numbers 50468,50469,50472,50473 ( Ernest Jarvis ) 50476, 50477, 50478, and 50479 who received new regimental numbers 40405,40406,40408,40409,40411,40412,40413 ( Ernest ) 40414. These men were;

FRED BORTON, CHARLES COOK, MATTHEW FAHMY, HENRY GAMBLE, WILLIAM HOLLOWAY, SID HARRIS, ERNEST JARVIS and FRED LAMBERT.

In January 1917 these former Suffolk men found themselves posted to a familiar part of the Somme. The 1st RDF war diary tells us that in January 1917 they occupied trenches around Carnoy and Guillemont somewhat ironic given that this is precisely the area where the new Dubliners had joined the Suffolks in May 1916. In January and early February 1917 it was a routine of marching backwards and forwards from billets in the village of Meute to the front line trenches at Guillemont. Towards the end of February they were involved in assault practice ready for an attack on the Potsdam trench at Sally Saillise.

The 1st Battalion RDF war diary WO95/2301 reports the attack of 28th February to 1st March in much graphic details as does the regimental history Neillís Blue Caps. Casualties were caused by our own barrage and there was fierce hand to hand fighting. Further difficulties were encountered by the usual problems of mud and the uncut wire and as a consequence the Dubliners were initially forced back. On 2nd March they were relieved having suffered 159 casualties. Haig wrote 'Congratulations 29th Division on success of minor operations carried out on the morning of 28th February'

The war was full of such minor operations causing numerous casualties and gaining little except to remind the enemy that they were the defenders waiting to be attacked . However, in the case of the Potsdam trench it appears even more of a hollow victory because within one month the Germans had withdrawn from the area fought over and retreated behind the heavily fortified Hindenburg Line. Not for the first time , many brave men had died in vain.

The RDF and 29th Division was now to be involved in the Battle of Arras which though less well known than the Somme or Ypres proved to be the shortest but most bloody of them all measured in terms of the daily rate of attrition.

The war diary tells us that in March the 1st battalion RDF was located around Ville sur Corbie in the south of the Somme involved in training and resting. The diary points out that the battalion was in a weak state so that each company was reduced to only two platoons During March and early April it received drafts of 321 ORs to bring it up to fighting strength.

By 12th April the battalion had reached Arras and was billeted in the Citadel. This may have been prophetic because this is the present location of the Memorial to the Missing of the battle of Arras upon whose walls some of the battalions names would appear. The battalion was not used in the early days of the battle but on 18th April it moved up to the front relieving the Lancashire Fusiliers in the village of Monchy le Preux. This fortified village like Thiepval before dominated the rolling Artois countryside and had proved a difficult nut to crack.

Monchy was captured after heavy fighting by a combination of the 37th infantry division and the cavalry on 11th April. The Germans had counter attacked and almost drove the British out had it not been for the Newfoundlanders (29th Division) who managed to hold it on 14th April. Their sacrifice is commemorated by the Caribou statue in the modern restored village of Monchy le Preux.

When the RDF occupied Monchy it was under constant heavy shell fire and it was extremely dangerous to move about. Casualties were frequent and the village was still full of the bodies of men and horses from the Essex Yeomanry who had been trapped and caught by the German artillery on 11th April. On the 21 April the 1st Dubliners were relieved and went back to sleep in the wet caves below the ruined city of Arras. The rest did not last long because on 23rd the battalion took over the eastern defenses of Monchy le Preux and were ordered to attack Infantry Hill at 4 30 pm on 24th April. However, a communications break down resulted in the attack going ahead without any artillery barrage. Companies W and X of the 1st Bn RDF went bravely forward but as the war diary describes they came under very heavy rifle and machine gun fire resulting in 80 killed or wounded and 37 missing.

The attack was a total failure and the battalion was withdrawn from the area to recover. Amongst the missing was private 40413 Ernest Jarvis, the reluctant soldier. The man who hated the experience of war had become another casualty.

I do not know when my great grandmother Lucy Jarvis was informed that her favourite son was missing but the Essex Chronicle newspaper of 6th July 1917 included his name in the wounded and missing column. I have been unable to find any evidence as to when it was confirmed that Ernest Jarvis had been killed. He has no known grave and is commemorated on the Arras Memorial to the Missing which includes 35000 names of men who died during April/May 1917 and March 1918 but have no known resting place. This beautiful memorial was designed by Sir Edward Lutyens and is located on the Arras ring road close by the Citadel in which Ernest and the Dubliners had first billeted on their arrival in Arras.

The panel for the RDF is in Bay 9 and contains the names of those who were killed and missing during their short engagement in the Battle of Arras. Earlier, I referred to 8 men who had been transferred from the 8th Suffolks to the RDF. Of these 8, three were killed and missing on 24th April 1917.

Sid Harris 40412 from South Norwood London aged 20, Fred Lambert 40414 from East Dulwich London aged 29 and Ernest Jarvis 40413 from Boreham Chelmsford Essex aged 27 (the CWGC citation says 25). All appear on the RDF panel in Bay 9.

Whilst Ernest has no CWGC headstone, his name is remembered on the Arras memorial and on the list of 1914 to 1919 dead in Chelmsford Cathedral.

Amazingly, his name and those of the others above appears in the Irelandís Memorial Records (IMR ). This was completed in 1922 and contains the names of 49000 men who fell in the Great War. These are listed in 8 beautifully illustrated printed volumes which can be found in the main libraries in Eire. I am indebted to Sean Connolly of the RDF association who provided me with the details of the IMR and also with a copy of the page which includes Ernest Jarvis. Thus, amongst the 49000 names are those of non Irishmen who had died whilst serving in an Irish regiment during WW1.

Those famous regiments like the Royal Dublin Fusiliers have long since gone following Irelandís independence but in the Garden of Remembrance in Westminster Abbey their names appear every year providing us all with an opportunity to remember all who served in them regardless of their nationality.

Ernestís death brought devastation to the Jarvis family of Boreham Essex. My grandmother and her many sisters would forever remember their gentle elder brother whom they always called Bunny. His wife May never remarried having been widowed only three months after their marriage and their daughter Beryl who was born in 1917 and died in 2009, never ever saw her father. She like thousands of others lived in a one parent family the awful legacy of the war that touched everyone.