Charles Brock

Charles Edward Brock was born on 19th November

1874, The son of John and Elizabeth Brock. John was a builder and

undertaker. The family consisted of five sons and one daughter.

Charles went to Rayne School, being admitted on 2nd January 1882, leaving on 11th May 1888.

The Brock family lived at The Firs - which of course was quite different to the way it looks now. Like a lot of what was called Rayne, The Firs was in the parish of Felstead.

The Brocks were a large family. Charles parents, John and Elizabeth, had eight children. Charles had two elder brothers and two elder sisters as well as three younger brothers.

In 1911 the Brock family was resident at

the Firs, Rayne:

John Brock - age 72 - Builder - born Felstead.

Elizabeth Brock - age 68 - born Felstead.

William Ernest Brock - age 40 - Carpenter - born Felstead.

Julia Annie Brock - age 38 - born Felstead.

Charles Edward Brock - age 36 - House Painter - born Felstead.

Charles enlisted in Dunmow into the Essex Yeomanry. Yeomanry was the term used to describe those units of the territorial army who were mounted on horses. Most of them came from the farming community where horses were extensively used and therefore the men were accustomed to riding.

The Essex Yeomanry was a Territorial Cavalry Regiment which was called up at the outbreak of War. It embarked for France in early 1915, and was stationed in the Ypres area.

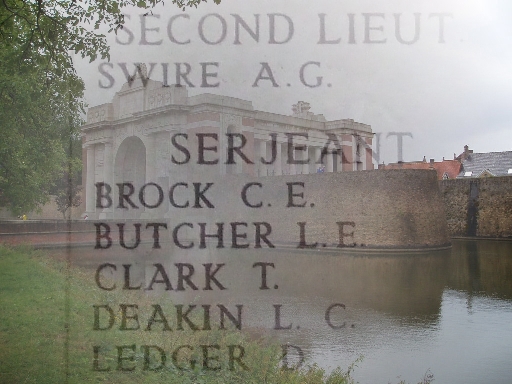

Charles was a Serjeant with the Essex Yeomanry.

He died aged 40 on 14th May 1915. He is remembered on the Menin Gate Memorial in Ypres.

On 12 May 1915, the Dunmow troop was stationed near Ypres. The following day, they were ordered to occupy front line trenches which had been lost to the Germans. The attack would be made on foot, the horses being left behind the front line.

The attack began at 2.15pm on 13th May. An attempt was made to slow the advance, as the British artillery was still shelling the German positions which meant firing over the heads of the Essex Yeomanry.

A party of around thirty Germans suddenly leapt from their trenches around two hundred yards in front of the Yeomanry and ran off. The Yeomanry left their trenches and charged after them. They were five minutes too early; the British artillery barrage, which was short of its target, was still in progress and the cavalrymen ran straight into it. Almost at the same time they came under fire from the Germans.

The survivors managed to reach the enemy trench and were soon passing round German cigarettes, bread and coffee. Before long powerful and extremely accurate fire descended on them. One of the Germans had stuck a small red flag on the parapet of the trench before retiring, and this was now being targeted by their artillery. Movement became impossible and the troops were effectively trapped in the trenches.

|

Heavy rain was falling, and the British rifles jammed in the mud. For two hours they had to withstand the bombardment. Between 4 and 5pm word came that the Yeomanry were to attempt to retire over the crest of the hill. One of the troopers subsequently wrote "The scene was awful. The cries of the wounded and dying were terrible. More than half the Regiment was killed, wounded or missing". In this one short battle, the Essex Yeomanry suffered heavy casualties both from German and British fire. 75 were killed and 86 wounded - 161 out of 302 men - over half the total force of the unit. One of those killed was Charles Brock who was amongst the older men, being aged 40.

Like so many others, Charles Brock's body could not be identified and so

he is commemorated on the famous Menin Gate at Ypres, the memorial

containing over 55,000 names of men who died in the area around the town

and who have no known grave.

As well as being commemorated at the Menin Gate, there is also a

memorial in Rayne, Braintree Baptist Church, and Chelmsford Cathedral.

|

|

The Essex Weekly News of May 21 1915 ran a special report on the action at YPRES, of which the following are extracts:

ESSEX YEOMANRY IN ACTION.

HEROIC CHARGE AT YPRES.

REPORTED HEAVY LOSSES.

Although no list of casualties in the Essex Yeomanry has been published officially, a number of letters received by relatives of men serving in the regiment go to show that they were engaged in severe fighting on Thursday, May 13th, and that the losses in killed, wounded and, missing are considerable.

One Correspondent, Trooper H. J. Tucker, writing to his father, who resides at Spelbrook, Bishops Stortford, states that when there was a roll call the casualties were found to be 168, and that included Col. Deacon, commanding, who is understood to be wounded and missing.

We have made an endeavour to compile a list based on information contained in private letters which have come to hand since Monday, and have taken every care possible in the difficult circumstances to ensure accuracy. The following names we obtained up to yesterday:-

(amongst those listed) Brock, Sergt., Rayne

After the list of names and any biographical notes the Weekly News dedicated two columns to reporting eye witness accounts. Again the following are extracts:

STORY OF DESPERATE FIGHTING.

HOW THE YEOMANRY MADE THE GERMANS RUN.

From the descriptions of the fighting written by those who took part in it to relatives and friends at home it is clearly evident that the Essex Yeomanry behaved in a very gallant manner. Officers and men alike distinguished themselves, behaving with all the cool and unflinching courage of their race. They made on May 13 a reputation for bravery of which the county has every reason to be proud, and their conduct is an inspiration to others.

THE STORY IN BRIEF.

It is possible from the early materials to obtain a general conception of the battle on this memorable day on which for the first time in the Great War a Territorial regiment belonging to Essex was under fire. The distinction, which deserves to become historic, will doubtless be cherished by the gallant Yeoman. Their conduct will enable every man now and hereafter to feel proud to serve in such a unit.

Leaving their horses in the rear the regiment were moved up to the firing line as infantry for the time being. On Wednesday night, May 12, they were employed in trench digging. The next day (Thursday, May 13) they occupied reserve trenches, being subjected for hours to a terrific bombardment by the German artillery. The British front-line trenches were smashed, and the reserve trenches occupied by the Yeomanry (who formed part of a British Brigade) became the foremost firing line.

THE ADVANCE OF THE BRITISH

In the afternoon, about half past two, orders were given for the British to advance. To do this the Essex Yeomanry had to charge across a space which was swept by rifles and machine guns. They managed to reach German trenches, driving the enemy out with the bayonet. Then they were counter-attacked, the captured trenches being heavily bombarded. It was at this period that most casualties occurred, and also later when the Yeomanry were ordered to retire, the object in view – to prevent a German advance – having been achieved.

"RAN LIKE HARES"

One account we received from a trustworthy source states that the Essex men charged to the fox-hunting cry and that the "Germans ran like hares" when they saw the British bayonets coming towards them.

VIVID ACCOUNT BY A DUNMOW TROOPER.

A vivid personal account of the battle is contained in a letter written last Sunday by Trooper Jack Mills to his father, Mr A. J. Mills, contractor, of Dunmow.

Trooper Mills is now in the Middlesex Hospital at Clacton, suffering

from injuries caused by a shell. He is only 18 years of age, and he

enlisted for the war upon the outbreak of hostilities. He belongs to the

Dunmow Troop, C Squadron. "I am once more in England," he begins, and

proceeds:-

I was in the terrible battle of Ypres, where the Essex Yeomanry lost so

many men. I was hit in the stomach by a piece of dirt thrown up by a

shell at my feet. How I came out alive I can’t think! The men who were

with us and have been all through the war from the retreat from Mons to

Neuve Chapelle said the battle of Ypres was ten times worse than

anything up till then.

STARTING FOR THE TRENCHES

I will try to give you a little account of the battle from the time we went into the trenches to the day I was sent away.

On the Tuesday we went from our billets to a place about four miles from Ypres. We marched 2½ miles, and spent Wednesday there in a dug-out. From the time we started we were shelled all the way.

On Wednesday evening we left our dug out and marched to the firing line to dig support trenches. To reach the line we had to march through Ypres, and as we passed through the city it was one mass of flames and was still being shelled. Dead horses and people lay all around in scores.

We reached our trenches and had so far only two wounded. We set to work digging, and had got fairly on the way when a German star shell gave us away. Instantly we knew what being under shell-fire was, but fortunately did not lose many men then.

We left those trenches and occupied trenches to the front line. It was then about midnight. We had some sleep until four o'clock, when the Germans commenced what our men described as "the most terrible bombardment during the war." They started at four in the morning and did not leave off until dark.

During this time our front line trench was blown up and occupied by the Germans under their own shell-fire. Our trench then became the firing line, and we began to get shells.

ORDERED TO CHARGE

Our section were on the look out, and a shell burst overhead and down went a chap on either side of me. They shelled our trench until it was no longer possible to hold it, and we retired to the right. This was at mid-day. The Germans still came on, and as things looked bad we were ordered to fix bayonets and charge.

Now, we had 400 yards of perfectly open ground to charge over, and the cannon and machine guns mowed us down like nine-pins. Then the charge slackened, but not for many seconds. On we went again, and next minute Lieut. Holt fell, and Major Roddick also fell back dead.

The remainder of us reached the parapet of the first German trench, but the Germans did not wait for the bayonet; they fled to their second trench. As we began to climb over the parapet our Colonel (Col. Deacon) and several others fell, and I also got laid one.

German supports then came up, and finding we had only twenty men in the captured German trench we tried to hold on until our other men could come up. Soon, however, our number was reduced to twelve, and the order was passed along "Every man for himself! Get back if you can!"

SLOWLY RETIRED

Crawling on our stomachs and taking cover behind our dead comrades, we slowly retired. All the time it was raining hard, and for every spot of rain a shell fell.

I and another chap, got half-way back, when we came across a pal of mine, shot through the groin and in terrible pain. The Germans were slowly overtaking us, but we lifted him up, and as we did so he got a bullet through his foot. We half-dragged and half-carried him to our lines, and then the Red Cross took him away.

We reached our own trenches again, and managed to hold them until the 19th Durham supported us, and then with another charge we captured our first lines, which had been blown up in the morning. It is said that more lives are lost in "No man's land" (a portion of the front before Ypres) than anywhere else. You get shelled on from all directions, and it is the perfect hell.

We went up to the trenches with 290 men, and at roll call on Friday there were only 78, but it is hoped that the others may have got with other regiments during the retirement.

However, we left the line in the same place we started, and we are not downhearted, except when we think of the fine fellows who fell that day for their country and their people at home.

Poor old Gowlett put his knee out again in the charge, but hung grimly on, and is now in hospital with me.

I don’t expect to be in hospital long, as the flesh was not pierced, but only bruised, and it shook me up a good deal.